Markets

News

Analysis

User

24/7

Economic Calendar

Education

Data

- Names

- Latest

- Prev

Signal Accounts for Members

All Signal Accounts

All Contests

France Trade Balance (SA) (Oct)

France Trade Balance (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

Euro Zone Employment YoY (SA) (Q3)

Euro Zone Employment YoY (SA) (Q3)A:--

F: --

Canada Part-Time Employment (SA) (Nov)

Canada Part-Time Employment (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)

Canada Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Full-time Employment (SA) (Nov)

Canada Full-time Employment (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Labor Force Participation Rate (SA) (Nov)

Canada Labor Force Participation Rate (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Employment (SA) (Nov)

Canada Employment (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)

U.S. PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Personal Income MoM (Sept)

U.S. Personal Income MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Core PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)

U.S. Core PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. PCE Price Index YoY (SA) (Sept)

U.S. PCE Price Index YoY (SA) (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Core PCE Price Index YoY (Sept)

U.S. Core PCE Price Index YoY (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Personal Outlays MoM (SA) (Sept)

U.S. Personal Outlays MoM (SA) (Sept)A:--

F: --

U.S. 5-10 Year-Ahead Inflation Expectations (Dec)

U.S. 5-10 Year-Ahead Inflation Expectations (Dec)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Real Personal Consumption Expenditures MoM (Sept)

U.S. Real Personal Consumption Expenditures MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

U.S. Weekly Total Rig Count

U.S. Weekly Total Rig CountA:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Weekly Total Oil Rig Count

U.S. Weekly Total Oil Rig CountA:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Consumer Credit (SA) (Oct)

U.S. Consumer Credit (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

China, Mainland Foreign Exchange Reserves (Nov)

China, Mainland Foreign Exchange Reserves (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Japan Trade Balance (Oct)

Japan Trade Balance (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Japan Nominal GDP Revised QoQ (Q3)

Japan Nominal GDP Revised QoQ (Q3)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Imports YoY (CNH) (Nov)

China, Mainland Imports YoY (CNH) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Exports (Nov)

China, Mainland Exports (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Imports (CNH) (Nov)

China, Mainland Imports (CNH) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Trade Balance (CNH) (Nov)

China, Mainland Trade Balance (CNH) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Exports YoY (USD) (Nov)

China, Mainland Exports YoY (USD) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Imports YoY (USD) (Nov)

China, Mainland Imports YoY (USD) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Germany Industrial Output MoM (SA) (Oct)

Germany Industrial Output MoM (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

Euro Zone Sentix Investor Confidence Index (Dec)

Euro Zone Sentix Investor Confidence Index (Dec)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada National Economic Confidence Index

Canada National Economic Confidence IndexA:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. BRC Like-For-Like Retail Sales YoY (Nov)

U.K. BRC Like-For-Like Retail Sales YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.K. BRC Overall Retail Sales YoY (Nov)

U.K. BRC Overall Retail Sales YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Australia Overnight (Borrowing) Key Rate

Australia Overnight (Borrowing) Key Rate--

F: --

P: --

RBA Rate Statement

RBA Rate Statement RBA Press Conference

RBA Press Conference Germany Exports MoM (SA) (Oct)

Germany Exports MoM (SA) (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. NFIB Small Business Optimism Index (SA) (Nov)

U.S. NFIB Small Business Optimism Index (SA) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Mexico 12-Month Inflation (CPI) (Nov)

Mexico 12-Month Inflation (CPI) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Mexico Core CPI YoY (Nov)

Mexico Core CPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Mexico PPI YoY (Nov)

Mexico PPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Weekly Redbook Index YoY

U.S. Weekly Redbook Index YoY--

F: --

P: --

U.S. JOLTS Job Openings (SA) (Oct)

U.S. JOLTS Job Openings (SA) (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M1 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M1 Money Supply YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M0 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M0 Money Supply YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M2 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M2 Money Supply YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Year (Dec)

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Year (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. EIA Natural Gas Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)

U.S. EIA Natural Gas Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

EIA Monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook

EIA Monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook U.S. API Weekly Gasoline Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Gasoline Stocks--

F: --

P: --

U.S. API Weekly Cushing Crude Oil Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Cushing Crude Oil Stocks--

F: --

P: --

U.S. API Weekly Crude Oil Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Crude Oil Stocks--

F: --

P: --

U.S. API Weekly Refined Oil Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Refined Oil Stocks--

F: --

P: --

South Korea Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)

South Korea Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Reuters Tankan Non-Manufacturers Index (Dec)

Japan Reuters Tankan Non-Manufacturers Index (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Reuters Tankan Manufacturers Index (Dec)

Japan Reuters Tankan Manufacturers Index (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index MoM (Nov)

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index YoY (Nov)

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland PPI YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland PPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland CPI MoM (Nov)

China, Mainland CPI MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Italy Industrial Output YoY (SA) (Oct)

Italy Industrial Output YoY (SA) (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

No matching data

Latest Views

Latest Views

Trending Topics

Top Columnists

Latest Update

White Label

Data API

Web Plug-ins

Affiliate Program

View All

No data

The 90-day temporary tariff reduction deal between the U.S. and China has triggered a sharp surge in imports, but analysts warn that reactive trade behavior may deepen long-term supply chain instability....

Switzerland has had productive talks with the US on the central bank’s currency interventions, Swiss National Bank President Martin Schlegel said, rejecting the suggestion that the country manipulates the franc’s exchange rate.

“We are no currency manipulator,” he said in Lucerne on Friday, adding that “we had a constructive conversation with the US authorities” on the topic.

Schlegel declined to further elaborate on the format or content of those talks, though a spokesperson later said that the SNB has an ongoing exchange with US authorities, especially with the Department of the Treasury.

The central bank chief pointed out that historically, the SNB has only ever intervened on the franc to meets its price stability directive.

“We have never influenced the exchange rate to get us an advantage,” he said. “We only acted to ensure we fulfill our mandate under the given global economic conditions.”

The franc is typically seen as a haven currency in times of market stress, with the recent market uncertainty triggered by US President Donald Trump’s tariff policy pushing it to a decade high against the dollar last month and near such a high against the euro.

The SNB’s past interventions earned Switzerland a currency manipulator tag during Trump’s first term, though that label was subsequently removed. Schlegel has repeatedly said that the threat of that classification won’t stop the institution from steering the currency if required.

By selling some of its own reserves in foreign denominations, the SNB can strengthen the exchange rate. In 2022 and 2023, it boosted the franc in this way to dampen domestic inflation by making imported goods cheaper.

For several years before that, it had used the mechanism in the opposite direction to keep a lid on the currency. This has seen the SNB’s balance sheet grow to a size some observers deem dangerous as it can yield large profits — as last year — but also large losses.

The latest data show that the Swiss central bank hardly stepped into currency markets in 2024. First-quarter numbers will be available at the end of June.

The SNB is just a month away from its next monetary policy decision, with markets and economists expecting a 25 basis-point reduction to zero at that meeting. Asked if officials may have to embrace negative rates, Schlegel said that “if the economic situation dictates that the interest rate needs to be at that level, then we will go there.”

Nvidia (NVDA.O), opens new tab is seeking a site in Shanghai for a research and development centre, three sources close to the matter said, reflecting the strategic significance of the Chinese market where U.S. curbs on advanced chip exports have hit sales.

The U.S. chipmaker began the search in early 2025 and is primarily evaluating locations in Shanghai's Minhang and Xuhui districts, one of the sources said.

The project gained momentum after a surprise visit to China by Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang last month, said two of the sources.

Huang, who has consistently said China is critical to Nvidia's growth, made his visit immediately after the U.S. placed new restrictions on China-bound shipments of its H20 chips, the only AI chip the company can sell legally in China.

Huang met senior Chinese officials, including Vice Premier He Lifeng and Shanghai's mayor Gong Zheng.

Reuters reported earlier this month that Nvidia plans to release a downgraded version of the H20 chip for China in the next two months, as it seeks to prop up sales in the country, where it has been lost market share to domestic rivals such as Huawei.

China generated $17 billion in revenue for Nvidia in the fiscal year ending January 26, accounting for 13% of the company's total sales.

The local government of Shanghai, which hosts China's largest foreign business community, including firms such as Tesla (TSLA.O), opens new tab, has expressed willingness to offer incentives for the Nvidia project, including tax reductions, said two of the sources.

The local authorities are also considering offering a substantial amount of land to Nvidia for its China R&D centre, one source added.

Nvidia declined to comment, while the Shanghai city government did not immediately respond to a request for comment. The sources declined to be named, as the plan is not public.

Following his visit to China, Huang told CNBC that the country's AI market could reach approximately $50 billion within the next two-to-three years.

He said that being excluded from this rapidly expanding sector would represent a "tremendous loss" for Nvidia, especially as competition with Huawei intensifies.

During an earnings call in February, before H20 chip sales to China were restricted, Nvidia executives said the company's sales to China were about half the level before U.S. export controls.

Since 2022, the U.S. government has imposed restrictions on the export of Nvidia's most advanced chips to China, citing concerns over potential military applications.

The Financial Times first reported on Friday about Nvidia's plan to build a R&D centre in China.

Israeli strikes on Gaza have killed more than 250 people since Thursday morning, local health authorities said on Friday, one of the deadliest phases of bombardment since a truce collapsed in March and with a new ground offensive expected soon.

The air and artillery strikes were focused on the northern section of the tiny, crowded enclave, where dozens of people including women and children were killed overnight, said Gaza Health Ministry spokesman Khalil al-Deqran.

Israel has intensified its bombardment and built-up armour along the border despite growing international pressure for it to resume ceasefire talks and end its blockade of Gaza, where an international hunger monitor has warned of famine.

U.S. President Donald Trump on Friday backed aid for the Palestinians, saying people in Gaza are starving and adding that he expected "a lot of good things" in the next month.

Asked whether he supported Israeli plans to expand the war in Gaza, Trump told reporters: "I think a lot of good things are going to happen over the next month, and we're going to see. We have to help also out the Palestinians. You know, a lot of people are starving on Gaza, so we have to look at both sides."

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said on May 5 that Israel was planning an expanded and intensive offensive against Hamas as his security cabinet approved plans that could involve seizing the entire Gaza Strip and controlling aid.

An Israeli defence official said at the time that the operation would not be launched before Trump concluded his visit to the Middle East, which is expected to end on Friday.

Israel's declared goal in Gaza is the elimination of Hamas, which attacked Israeli communities on October 7, 2023, killing around 1,200 people and seizing about 250 hostages.

Its military campaign has devastated the enclave, pushing nearly all inhabitants from their homes and killing more than 53,000 people according to Gaza health authorities, while aid agencies say its blockade has caused a humanitarian crisis.

Heavy strikes on Friday were reported in the northern town of Beit Lahiya and in the Jabalia refugee camp, where Palestinian emergency services said many bodies were still buried in the rubble.

Israel's military said its air force had struck more than 150 targets across Gaza, saying these included anti-tank missile posts, terrorist cells, military structures and operational centres.

In Jabalia camp in the northern Gaza Strip, men picked through a sea of rubble following the night's strikes, pulling out sheets of metal as small children clambered through the debris.

Around 10 bodies draped in white sheets were lined up on the ground before being taken to hospital. Women sat crying nearby and one lifted a corner of a sheet to gaze at the dead person's face.

Ismail, a man from Gaza City who gave only his first name, described a night of horror. "The non-stop explosions resulting from the airstrikes and tank shelling reminded us of the early days of the war. The ground didn't stop shaking underneath our feet," Ismail told Reuters via a chat app.

"We thought Trump arrived to save us, but it seems Netanyahu doesn't care, neither does Trump," he added.

Israel has faced increasing international isolation over its campaign in Gaza, with even the United States, its staunchest ally, expressing unease over the scale of the destruction and the dire situation caused by its blockade on the delivery of food and other vital aid.

On Thursday, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said Washington was "troubled" by the humanitarian situation in the enclave.

Netanyahu has dispatched a team to Doha to take part in ceasefire talks with Qatari mediators but he has ruled out concessions, saying Israel remains committed to defeating Hamas.

The Hostages and Missing Families Forum, which represents some of the families and supporters of the 58 hostages still held in Gaza, said that Israel risked missing a "historic opportunity" to bring them home as Trump wound up his visit to the Middle East.

"We are in dramatic hours that will determine the future of our loved ones, the future of Israeli society, and the future of the Middle East," the group said in a statement.

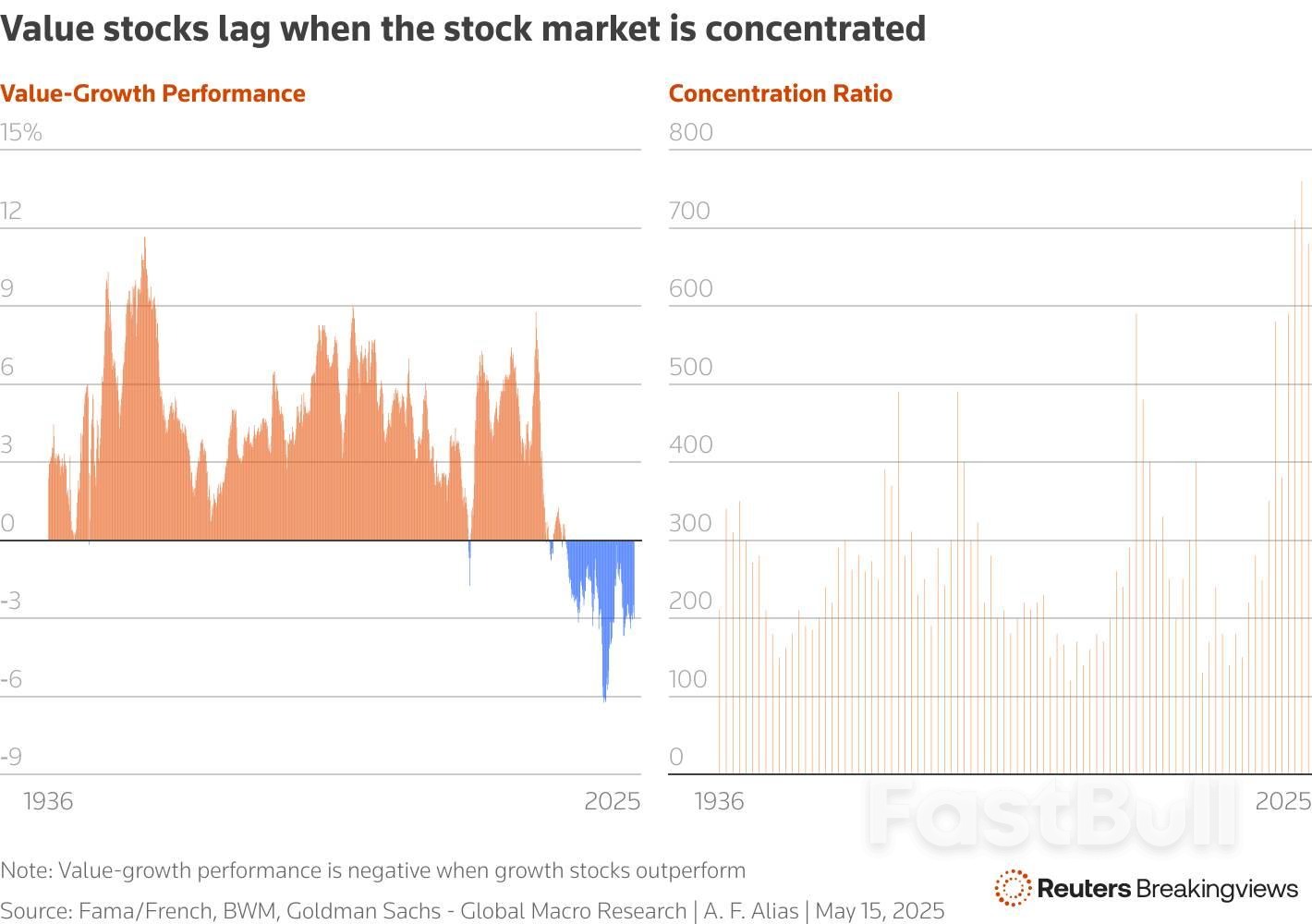

Warren Buffett, the greatest investor of all time, has announced his retirement. Fellow value investors are in a state of shock. Unfortunately, they have more serious problems to consider. For years, their favoured investment style has been out of fashion. Clients have lost patience. In a world in which the U.S. stock market index has delivered consistently outsized returns, low-cost funds that passively track an index seem a no-brainer. Yet the prospects for value investors have always been always brightest when the rest of the world loses faith.

Over the very long run, buying equities at relatively cheap valuations has worked out well. Economists Eugene Fama and Ken French define value as a low ratio of share price to book value. Using this measure, U.S. value stocks have beaten growth stocks, which have high price-to-book ratios, by 2.5% a year since 1926. Value has also outperformed in most other overseas markets, according to the UBS Global Investment Returns Yearbook compiled by Elroy Dimson, Paul Marsh and Mike Staunton. Its luck ran out, however, on the eve of the global financial crisis. Between 2007 and 2020, growth beat value. The latter recovered some ground in 2020 but fell back again after the “Magnificent Seven” big technology stocks took off in late 2022.

It is important to note that price to book is not the metric contemporary value investors rely upon. Warren Buffett’s partner, the late Charlie Munger, taught him to consider a firm’s competitive position – what the Oracle of Omaha called the “moat.” If a business consistently earns above average returns on capital, investors can safely buy its shares at a premium multiple to the rest of the market. Furthermore, the balance sheet value of a company’s assets is not a reliable measure of value, since it excludes many intangible assets such as research and development. Share buybacks and acquisitions further distort accounting book value.

Still, there are other investment oddities to consider. Small-cap stocks, which historically have beaten larger rivals and provide a favourite hunting ground for value investors, have also had a dismal run. Global stock markets, both the developed and emerging variety, have been trounced by the extraordinary performance of U.S. stocks. Between 2010 and the start of this year, American equities had delivered annualised returns of 10% after inflation, according to UBS. Over the same period, the other stock markets have collectively returned 2.6% a year after inflation. Emerging markets returned just half that figure. Howard Marks, the veteran value investor and co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, laments that “all norms have been overturned.”

The hard times for value investing can be explained by various factors. First, ultra-low interest rates after the global financial crisis increased the appeal of growth stocks whose profits lie in the distant future. Higher-yielding value stocks were relatively disadvantaged.

Second, value investors have suffered from the rapid expansion of index investing. Nearly 60% of the U.S. stock market is currently held by funds that passively track a benchmark. Goldman Sachs forecasts that between 2014 and 2026 the cumulative outflows from U.S. actively managed equity mutual funds into passive vehicles will reach around $3 trillion. As indexation advances, investors dump the value and small-cap stocks owned by traditional fund managers in favour of the S&P 500 Index (.SPX), opens new tab, which is heavily weighted towards larger and more expensive stocks.

The United States is home to the largest and most profitable companies the world has ever seen. The outsized returns of the Magnificent Seven over the last decade have depressed the relative returns of both value stocks and small caps. By the end of last year, the U.S. stock market had become more concentrated than at any time since the 1930s. Georg von Wyss, a portfolio manager at Zurich-based firm BWM, observes that in the past periods of extreme market concentration have been accompanied by the underperformance of value stocks. This was the case during the “Nifty Fifty” boom of the early 1970s and again in the technology bubble of the late 1990s.

Towards the end of that craze, value stocks were exceedingly cheap relative to the overall market. Clients closed their accounts with underperforming investment firms. Several well-known value managers were either fired or took early retirement. Warren Buffett, who didn’t partake in the market frenzy, was deemed to have lost the plot. But when the boom turned to bust and market concentration declined, as it did in 1975 and 2000, value stocks outperformed for years. Could value investors be on the verge of yet another winning streak?

The turmoil of the early months of Donald Trump’s second term may signal such a shift. At the London Value Investor Conference on Wednesday Richard Oldfield of Oldfield Partners said that the new U.S. administration, with its on-off threat of tariffs and hostile rhetoric to erstwhile allies, poses a risk to trend of “American exceptionalism”. Sensing the loss of U.S. support, Germany is borrowing to invest in defence and infrastructure. If capital flows to the United States start to reverse, developed and emerging stock markets stand to benefit. Value rallies have repeatedly petered out in recent years but, says Oldfield, “this time is different.”

Other headwinds that have buffeted value investors over the past decade may also be about to disperse. Over the past three years, interest rates have returned to more normal levels. The Magnificent Seven are currently locked in an arms race to invest in artificial intelligence. Time will tell whether their vast capital spending delivers an adequate return. These megacap growth stocks have underperformed in the year to date. Meanwhile, value and small-cap stocks in the United States and elsewhere offer exceptional opportunities.

Last year, David Einhorn of Greenlight Capital pronounced that value was “dead, opens new tab”. Another speaker at the London conference, Alissa Corcoran of Kopernik Global Investors refutes this claim. Value investing is immortal, she says. As index funds absorb a greater share of the world’s stock market, fundamental investors are still needed to perform the vital role of price discovery. Ideally, such investors would exhibit a patient, long-term approach and not be swayed by the herd. They should be careful stewards of their clients’ capital, and, above all, be endowed with common sense. Warren Buffett displayed these virtues to an uncommon degree. He will be missed. But there are legions of value investors ready to fill the void.

In a recent column, I argued that US managers have much to learn from emerging markets. Today, I want to add that managers everywhere have much to learn from the interwar years.

The interwar period — marked by the turmoil of the 1920s and the depression of the 1930s — was the last great period of deglobalization. The century between the defeat of Napoleon in 1815 and the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 was an era of pell-mell globalization. International trade grew by 3.5% a year. The gaps in commodity prices between continents declined by four-fifths. Sixty million Europeans migrated to the US. In 1913, foreign direct investment was 9% of world output, a proportion that wasn’t equaled until the 1990s.

The interwar years replaced seemingly unstoppable globalization with seemingly unstoppable deglobalization. The US had never shared Britain’s cast-iron commitment to free trade — in 1870 America, tariffs of 50% were common — but between the wars, protectionism became rampant. Governments not only increased and extended tariffs but also put a near halt to immigration. The annual migration rate to the US fell from 11.6 immigrants per thousand in the first decade of the 20th century to 0.4 per thousand in the 1940s.

European countries responded with tariffs of their own. Governments abandoned gold and imposed currency controls. The Mexican government nationalized foreign oil companies. By the late 1930s, half the world’s trade was restricted by tariffs, and the world was divided into currency blocs. Deglobalization gathered momentum despite the emergence of new technologies such as airplanes, automobiles, telephones, and ocean liners that were relentlessly killing distance.

Multinationals adopted three main strategies to cope with this world of deglobalization and political instability.

The first was to jump over tariff barriers and currency restrictions by establishing powerful foreign subsidiaries. American companies led the way partly because they were so well managed and partly because the US government made life so difficult for foreign companies, particularly banks.

This produced paradoxical results. The number of multinationals increased even as the world fragmented. But successful multinationals put down deep global roots. “The national autonomy of subsidiaries grew as they were closer to the local market and local politicians,” says Geoffrey Jones, a professor at Harvard Business School and author of Multinationals and Global Capitalism. “They unwound global supply chains and produced more stuff locally.” General Motors purchased Opel, one of Germany’s 10 largest industrial companies, and Vauxhall, a smaller British company, and employed local managers to run them. American Home Products, a giant US pharmaceuticals company, rolled up several smaller British firms. Coca-Cola sponsored the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin.

The second was to use institutional innovation to compensate for political turbulence. Many companies coped with the most obvious downsides of fragmentation, falling demand and unpredictable supply, by either consolidation or coordination. Giant new companies such as Germany’s IG Farben and the UK’s Imperial Chemical Industries in chemicals, Unilever (a merger of Dutch margarine producer Unie with the British soap maker Lever Brothers) in consumer goods and Shell in petrol formed from the merger of smaller companies. Cartels appeared in a wide range of markets (tea, tin, coffee, gold and diamonds, electric lights and matches) either to control prices or divvy up the world into separate spheres. Cartelization produced some of the world’s most powerful companies, such as the Anglo-American Corporation and De Beers in South Africa, and some of its most enduring price-fixing arrangements, such as the Tin Producers Association, which was started in 1929 and only wound up in 1985. The Swiss-registered Electric Light Consortium controlled three-quarters of the global supply of electric lights and was itself controlled from behind the scenes by America’s General Electric, which wasn’t even a member.

Others adopted a new institutional form: the multidivisional firm or “M form” for short. General Motors pioneered the M form under Alfred Sloan’s leadership as a way of coping with the fragmentation of the consumer market: Powerful product managers were given control of producing different models for different consumer markets (Cadillac for the rich and so on down the income pyramid). But that approach turned out to be equally appropriate for a fragmenting geographical market. Both US and German behemoths began devolving enormous operational power to regional managers and restricting the headquarters to producing broad strategic plans.

The third was to treat regional fragmentation as a business opportunity rather than as a barrier to global ambitions. British companies such as Cadbury’s in chocolate and Dunlop in rubber focused on securing supplies and markets across the British Empire and the wider Commonwealth. Barclays purchased banks across Africa. Ford purchased a rubber plantation in Brazil and the United Fruit Company tightened its grip on South American bananas. State-allied oil companies such as Britain’s Anglo-Persian and America’s Standard Oil battled for control of supplies in the disputed Middle East, with plenty of help from the secret services.

Harvard’s Jones is struck by the similarity between today and the 1930s, with technologies working to bring the world together and policy makers and parts of the electorate pushing in the opposite direction. “The first lesson of history,” he says, “is that politics always matters more than technology in the direction of travel.” This means, in my view, that companies would be wise to abandon their “one world” strategies from the heady years of globalization and instead reorganize themselves into federations of national firms that can respond to local circumstances and, if necessary, pretend to be local companies. They also need to embrace anything from mergers to alliances that will give them the bulk to deal with collapses in demand or interruptions in supply: The more unpredictable markets become, the more companies need to do things internally.

But these years contain some powerful moral as well as practical lessons. CEOs can’t be expected to sacrifice their businesses to defend social or political causes of the day far outside their realm of operations. But there are limits to what they ought to tolerate. Some of America’s most successful companies placed no limits on how far they would go to get German business in the 1930s. General Motors’ Opel produced trucks for the Nazi war machine; IBM worked so closely with the Nazi regime that its boss, Thomas J. Watson Sr., was awarded the Order of the German Eagle in 1937. CEOs will be judged by their investors on how well they adapt to a rapidly deglobalizing world, but they will also be judged by history if they lose their moral compass in order to bow to the will of autocrats and scoundrels.

Ether's ETH$2,616.44 rally, though impressive, leaves much to be desired. That's because the unwinding of shorts is said to be fueling the rally, not fresh longs or bullish leveraged bets on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME).

"The rally is primarily the result of short covering – traders unwinding bearish positions – rather than a surge of bullish conviction," Sui Chung, CEO of crypto index provider CF Benchmarks, told CoinDesk. CME's derivatives, preferred by institutions, track the CF Benchmarks' Bitcoin Reference Rate – New York (BRRNY) variant.

When bears cover their shorts, it means they are buying back futures contracts initially sold. This action of short covering temporarily boosts demand in the market, putting upward pressure on prices.

Chung pointed to the still-low CME futures premium (basis) as evidence that the rally is led by short covering.

While ether's spot price has surged nearly 90% to above $2,600 since the early April sell-off, the annualized one-month basis in the CME's ether has held flat between 6% and 10%, according to data source Velo.

"In more conventional setups, we would expect rising basis levels if traders were initiating fresh longs with leverage," Chung noted. "It's a reminder that not all rallies are fueled by new demand; sometimes, they reflect repositioning and risk reduction."

One might argue that the basis has held steady due to sophisticated trades "arbing" away the price difference between the CME ETH futures and the spot index price by shorting futures and buying ETH spot ETFs.

That argument looks weak when considering the U.S.-listed spot ETFs have seen net positive inflows on just ten trading days in the past four weeks. Besides, net inflows tallied over $100 million just once, according to the data source SoSoValue.

"The lack of inflows into ETH ETFs and the muted basis paints a different picture, this latest move higher doesn't appear to be driven by new leveraged longs," Chung said.

White Label

Data API

Web Plug-ins

Poster Maker

Affiliate Program

The risk of loss in trading financial instruments such as stocks, FX, commodities, futures, bonds, ETFs and crypto can be substantial. You may sustain a total loss of the funds that you deposit with your broker. Therefore, you should carefully consider whether such trading is suitable for you in light of your circumstances and financial resources.

No decision to invest should be made without thoroughly conducting due diligence by yourself or consulting with your financial advisors. Our web content might not suit you since we don't know your financial conditions and investment needs. Our financial information might have latency or contain inaccuracy, so you should be fully responsible for any of your trading and investment decisions. The company will not be responsible for your capital loss.

Without getting permission from the website, you are not allowed to copy the website's graphics, texts, or trademarks. Intellectual property rights in the content or data incorporated into this website belong to its providers and exchange merchants.

Not Logged In

Log in to access more features

FastBull Membership

Not yet

Purchase

Log In

Sign Up