Markets

News

Analysis

User

24/7

Economic Calendar

Education

Data

- Names

- Latest

- Prev

Signal Accounts for Members

All Signal Accounts

All Contests

France Trade Balance (SA) (Oct)

France Trade Balance (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

Euro Zone Employment YoY (SA) (Q3)

Euro Zone Employment YoY (SA) (Q3)A:--

F: --

Canada Part-Time Employment (SA) (Nov)

Canada Part-Time Employment (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)

Canada Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Full-time Employment (SA) (Nov)

Canada Full-time Employment (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Labor Force Participation Rate (SA) (Nov)

Canada Labor Force Participation Rate (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Employment (SA) (Nov)

Canada Employment (SA) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)

U.S. PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Personal Income MoM (Sept)

U.S. Personal Income MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Core PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)

U.S. Core PCE Price Index MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. PCE Price Index YoY (SA) (Sept)

U.S. PCE Price Index YoY (SA) (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Core PCE Price Index YoY (Sept)

U.S. Core PCE Price Index YoY (Sept)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Personal Outlays MoM (SA) (Sept)

U.S. Personal Outlays MoM (SA) (Sept)A:--

F: --

U.S. 5-10 Year-Ahead Inflation Expectations (Dec)

U.S. 5-10 Year-Ahead Inflation Expectations (Dec)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Real Personal Consumption Expenditures MoM (Sept)

U.S. Real Personal Consumption Expenditures MoM (Sept)A:--

F: --

U.S. Weekly Total Rig Count

U.S. Weekly Total Rig CountA:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Weekly Total Oil Rig Count

U.S. Weekly Total Oil Rig CountA:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Consumer Credit (SA) (Oct)

U.S. Consumer Credit (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

China, Mainland Foreign Exchange Reserves (Nov)

China, Mainland Foreign Exchange Reserves (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Japan Trade Balance (Oct)

Japan Trade Balance (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Japan Nominal GDP Revised QoQ (Q3)

Japan Nominal GDP Revised QoQ (Q3)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Imports YoY (CNH) (Nov)

China, Mainland Imports YoY (CNH) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Exports (Nov)

China, Mainland Exports (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Imports (CNH) (Nov)

China, Mainland Imports (CNH) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Trade Balance (CNH) (Nov)

China, Mainland Trade Balance (CNH) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Exports YoY (USD) (Nov)

China, Mainland Exports YoY (USD) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Imports YoY (USD) (Nov)

China, Mainland Imports YoY (USD) (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

Germany Industrial Output MoM (SA) (Oct)

Germany Industrial Output MoM (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

Euro Zone Sentix Investor Confidence Index (Dec)

Euro Zone Sentix Investor Confidence Index (Dec)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada National Economic Confidence Index

Canada National Economic Confidence IndexA:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. BRC Like-For-Like Retail Sales YoY (Nov)

U.K. BRC Like-For-Like Retail Sales YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.K. BRC Overall Retail Sales YoY (Nov)

U.K. BRC Overall Retail Sales YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Australia Overnight (Borrowing) Key Rate

Australia Overnight (Borrowing) Key Rate--

F: --

P: --

RBA Rate Statement

RBA Rate Statement RBA Press Conference

RBA Press Conference Germany Exports MoM (SA) (Oct)

Germany Exports MoM (SA) (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. NFIB Small Business Optimism Index (SA) (Nov)

U.S. NFIB Small Business Optimism Index (SA) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Mexico 12-Month Inflation (CPI) (Nov)

Mexico 12-Month Inflation (CPI) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Mexico Core CPI YoY (Nov)

Mexico Core CPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Mexico PPI YoY (Nov)

Mexico PPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Weekly Redbook Index YoY

U.S. Weekly Redbook Index YoY--

F: --

P: --

U.S. JOLTS Job Openings (SA) (Oct)

U.S. JOLTS Job Openings (SA) (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M1 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M1 Money Supply YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M0 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M0 Money Supply YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M2 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M2 Money Supply YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Year (Dec)

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Year (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. EIA Natural Gas Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)

U.S. EIA Natural Gas Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)

U.S. EIA Short-Term Crude Production Forecast For The Next Year (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

EIA Monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook

EIA Monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook U.S. API Weekly Gasoline Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Gasoline Stocks--

F: --

P: --

U.S. API Weekly Cushing Crude Oil Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Cushing Crude Oil Stocks--

F: --

P: --

U.S. API Weekly Crude Oil Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Crude Oil Stocks--

F: --

P: --

U.S. API Weekly Refined Oil Stocks

U.S. API Weekly Refined Oil Stocks--

F: --

P: --

South Korea Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)

South Korea Unemployment Rate (SA) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Reuters Tankan Non-Manufacturers Index (Dec)

Japan Reuters Tankan Non-Manufacturers Index (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Reuters Tankan Manufacturers Index (Dec)

Japan Reuters Tankan Manufacturers Index (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index MoM (Nov)

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index YoY (Nov)

Japan Domestic Enterprise Commodity Price Index YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland PPI YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland PPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland CPI MoM (Nov)

China, Mainland CPI MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

No matching data

Latest Views

Latest Views

Trending Topics

Top Columnists

Latest Update

White Label

Data API

Web Plug-ins

Affiliate Program

View All

No data

The latest upheaval is also likely to have curbed output — a number of shops and businesses across the country shut their doors while the protests were underway, and some in central Nairobi were ransacked, looted and burned.

Kenya was racked by nationwide protests and clashes that left at least 16 people dead and hundreds injured in late June.

The violence erupted after thousands took to the streets to mark the anniversary of demonstrations held last year against proposed tax increases. Those protests culminated in the storming of parliament and more than 60 people being killed before the government backpedaled.

The discord has been fueled by repeated allegations of police brutality and the misappropriation of public funds, and pressures from high unemployment and living costs. The gulf between citizens and the authorities are a setback to any ambitions President William Ruto may have of seeking a second term in 2027.

Kenyans, who were already reeling from a cost-of-living crisis and angered by politicians flaunting their wealth, were outraged by the government’s plan to impose new taxes on a wide range of items, including staples such as bread and diapers. The duties had been proposed to reduce the budget deficit and unlock support from the International Monetary Fund.

Most of the protesters were Kenyans in their 20s and 30s. After initially just urging for the levies to be revoked, the demonstrators widened their demands, calling for an end to deep-rooted corruption and wastage of taxpayer money, and justice for those who were killed in the marches.

The police used teargas, water cannons and live bullets to disperse the crowds. Most of the fatalities occurred on June 25 of last year, when thousands of people stormed parliament.

After initially accusing the protesters of treason, Ruto bowed to public pressure, refusing to sign the controversial tax bill passed by lawmakers — although several of the levies were subsequently reintroduced, raising public ire. He also named a new cabinet that for the first time since 2008 comprised members of both the ruling coalition and the opposition.

They came to pay their respects to those who were killed in last year’s marches and express their anger about the lack of accountability. Authorities have only prosecuted two cases over the 2024 fatalities, according to the Independent Policing Oversight Authority.

There were also separate protests against extra-judicial killings and the abduction and torture of political activists and government opponents.

Interior Secretary Kipchumba Murkomen labeled the latest demonstrations “terrorism disguised as dissent” and vowed to punish the orchestrators.

The police again reacted with a heavy hand, using live bullets to disperse people who came to light commemorative candles in the port city of Mombasa. They also fired teargas at relatives of those who died last year, who had planned to lay wreaths at parliament in the capital, Nairobi.

The authorities instructed the media to halt live coverage of the protests and threatened regulatory action if broadcasters didn’t comply. The Kenya Editors Guild said this directive was a violation of the constitution and an affront to press freedom and public accountability. The high court subsequently froze the order.

Kenya is East Africa’s biggest economy but its gross domestic product only grew by 4.7% in 2024, the slowest pace since the Covid-19 pandemic. The protests partially offset the benefits of improved harvests.

The latest upheaval is also likely to have curbed output — a number of shops and businesses across the country shut their doors while the protests were underway, and some in central Nairobi were ransacked, looted and burned.

The unrest may complicate the government’s efforts to address its deteriorating fiscal position and secure a new support program from the IMF. A previous deal was abandoned after the scrapping of the tax increases resulted in the country failing to reach the fiscal-deficit targets set by the lender.

Ruto’s reputation has been scarred and his popularity has taken a hit. A number of the demonstrators called for him to resign or only serve a single term.

“Ruto’s political capital remains weak and ongoing controversial police violence will only weaken his political standing,” risk consultancy Eurasia Group said in a note. However, it added that the protests are unlikely to be destabilizing or sustained.

The likelihood of the president being forced from office prior to the election due in 2027 isn’t high. In March, Ruto entered an alliance with former Prime Minister Raila Odinga, previously his main rival, and there’s no obvious candidate to replace him.

Corporate America’s profits are slipping. Last week, the Bureau of Economic Analysis confirmed that corporate post-tax profits dropped in the first quarter by 3.3% — by far their biggest fall since the pandemic.

When companies make less money, it’s often a harbinger of an economic slowdown. In this case, it also raises the more profound question of whether the Trump 2.0 agenda is deliberately aimed at companies’ bottom line.

This sounds outlandish. The stock market is on the brink of an all-time high, so Corporate USA is worth more than ever. But it makes sense. After-tax profits account for an unprecedented 10.7% of gross domestic product, when in the last 50 years of the 20th century, they never exceeded 8%. The only time approaching their current share of the economy was in 1929 on the eve of the Great Crash. If the nation is to deal with inequality, money must be redistributed from somewhere; corporate profits are an obvious source of funds.

Elements in the Trump coalition have long held an anti-corporate agenda. A few months ago, Adrian Wooldridge argued in this space that MAGA wanted to “end capitalism as we know it.” Specifically, he contended that many leaders in the Trump coalition wanted to “deconstruct the great workhorse of American capitalism: the publicly owned and professionally managed corporation.”

These are strong words, but sound understated compared to the writings of Kevin Roberts, head of the Heritage Foundation and a lead creator of Project 2025, an ambitious and radical agenda for Trump 2.0. He argues that BlackRock, the world’s largest fund manager and a pillar of contemporary US capitalism, is “decadent and rootless” and should be burned to the ground — a fate it should share with the Boy Scouts of America and the Chinese Communist Party.

For Marjorie Taylor Greene, an outspoken Trump supporter in Congress, “the way corporations have conducted themselves, I’ve always called it corporate communism.” She has urged government investigations of companies that stopped donations to Republicans after the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on Congress.

Steve Bannon, Trump’s campaign chief in 2016, complained to Semafor that only $500 billion of the US government’s $4.5 trillion came from corporate taxes. “Since 2008, $200 billion has gone into stock repurchases. If that had gone into plants and equipment, think what that would have done for the country.”

He advocated a “dramatic increase” in taxes on corporations and the wealthy. “For getting our guys’ taxes cut, we’ve got to cut spending, which they’re gonna resist. Where does the tax revenue come from? Corporations and the wealthy.”

Several current policies are not explicitly anti-corporate, but more or less guaranteed to have that effect.

Michel Lerner, head of the HOLT analytical service at UBS, points out that in data going back to 1870, the correlation between tariffs and companies’ earnings yield (a measure of their core profitability) has been consistent. Tariffs hurt companies. Looking at the cash flow return on investment since 1950, it has risen (meaning companies grew more profitable) directly in line with rises in imports as a proportion of GDP.

Research done jointly by Societe Generale Cross-Asset and Bernstein demonstrates that globalization has benefited US companies not only through international sales (40% of revenues for S&P 500 companies) but also through lower costs. In 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organization, the S&P’s cost of goods sold accounted for 70% of the revenues generated by selling them. It had been around this level for many years. That has now dropped to 63% — a massive improvement of 7 percentage points in this basic margin. Technology, consumer and industrial firms have gained the most — and stand to lose the most from deglobalization.

Trump 2.0 policies so far have redistributed from shareholders to workers. Vincent Deluard, macro strategist at StoneX Financial, points out that the only tax not cut by the One Big Beautiful Bill currently before Congress is corporate income tax. “The grand bargain of the Big Beautiful Bill is to compensate for the tariffs’ inflationary shock with personal income tax cuts,” he says. “If exchange-rate adjustments, foreigners, and consumers do not pay for tariffs, corporate profits will.”

Beyond that, eliminating illegal immigration and restricting foreign students raises labor costs. Threats to tax foreign investments in section 899 of the bill — which now appear likely to be withdrawn — risked reducing capital inflows and make it harder to raise finance.

Corporations’ own behavior has contributed to these trends. Over history, their share of GDP has tended to oscillate with the economy, rising when labor organizations’ negotiating power is weak. But in this century, their profits grew less susceptible to the economic cycle, surging higher after the pandemic.

Albert Edwards, a macro strategist for SocGen, argues that they pushed through margin-expanding price increases “under the cover of two key events, namely 1) supply constraints in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic, and 2) commodity cost-push pressures after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.”

Margins matter more in an environment where people are conscious of the damage inflation can do to their standard of living. That gave rise to the concept of “greedflation” — which Edwards thinks is deserved. Politicians have increasingly felt emboldened to intervene in companies’ pricing decisions, something that’s been off-limits since Richard Nixon’s ill-fated price controls in the early 1970s. Kamala Harris proposed “anti-gouging” policies in her unsuccessful presidential campaign; more recently, Trump forced a climbdown by companies like Amazon that proposed to itemize the impact of tariffs on the prices they charged.

Rising to the top of a company never used to be a ladder to mega-wealth. That was reserved for entrepreneurs who founded their own firms. Modern executive pay has changed that and allowed CEOs to become billionaires by meeting unchallenging targets for their share price. The gulf between their pay and workers’ wages shrieks of injustice; according to the Economic Policy Institute, the CEO-to-worker compensation ratio reached 399-1 in 2021; in 1965, it was only 20-1. From 2019 to 2021, CEO pay rose 30.3% while those workers who kept their jobs through the pandemic got a raise of 3.9%.

This can easily be dismissed as the politics of envy, but executive compensation now arguably skews the entire economy. Andrew Smithers, a veteran London-based fund manager and economist, and nobody’s idea of a leftist, has long inveighed against the bonus culture, which he holds responsible for a disastrous misallocation of capital.

Smithers argued that America’s problem was “two decades of underinvestment”:

He argues that companies increased their investment in response to corporate tax cuts in earlier generations, but stopped doing this once executives were paid to prioritize their share price. That led them to cut back on investment, spending money on acquisitions and share buybacks. That dampened growth, but also ensured better returns in the short run for shareholders.

As investing in stocks is still primarily a game for those who are already wealthy, this stoked inequality still further. Opposition to high executive pay is often couched as a populist class-warrior position, but there is far more to it than that.

The Trump coalition always had anti-corporate elements, but this didn’t stop his first administration from delivering for the private sector in a big way. In 2024, Trump added the support of Silicon Valley, and took the oath of office for the second time in front of a serried rank of billionaires. But he’s also losing old corporate supporters.

Charles Koch, the industrialist hated by Democrats as the architect of libertarian Republican policies, has lost patience. After funding Nikki Haley’s run against Trump in last year’s Republican primaries, he told the Cato Institute earlier this year that too many institutions had lost their libertarian principles, and “people have forgotten that when principles are lost, so are freedoms.” How will people like Koch respond if the administration clamps down on companies?

America’s key political developments tend to happen within parties, not between them. The current Republican coalition is no stranger in concept than Lyndon Johnson’s Democratic Party of the 1960s, the New Deal coalition that combined multi-racial liberals from the North and West with pro-segregationist whites from the South. Once Johnson decided to choose one wing over the other, with his civil rights acts, that alliance disintegrated.

For now, the MAGA coalition includes both America’s largest corporations and their most trenchant critics. The policy choices of the next few months, and their effects, will determine whether that can continue.

Tariffs and an effort to reduce federal expenditures should help offset increases to the U.S. deficit pile stemming from President Donald Trump’s massive tax-and-spending bill, according to analysts at ING.

In a note to clients, the analysts argued that the Trump-backed "One Big Beautiful Bill Act," which would extend tax cuts from 2017 while raising expenditures on defense and border security, is "on the face of it, [...] a huge fiscal giveaway."

They noted that the Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the package will lower tax revenues by $3.7 trillion over the next 10 years, while its proposed spending cuts to some programs would save just $1.3 trillion, "leaving the primary deficit $2.4 trillion wider than would otherwise have been the case."However, the analysts noted that Trump’s aggressive tariff agenda is already generating tax revenues that are separate from the fiscal package, adding on to a little under $200 billion in savings already registered by reduction measures carried out by the Department of Government Efficiency.

Yet "while these initiatives may fill the financial hole created by ’One Big Beautiful Bill Act,’ U.S. deficits will remain wide and debt levels will continue to grow, especially when we consider the continuous 0.1-0.2 percentage point GDP increase in demography-related spending and how that will feed into the U.S.’s fiscal position," the ING analysts said.

"Moreover, the combination of these policies is likely to be detrimental to economic growth in the near term, which runs the risk of official deficit and debt projections being too optimistic."

The Trump administration has touted the bill as a means to boost small businesses, families and American workers. Among a myriad of measures, the legislation includes a push to put Medicaid on a more sustainable footing and efforts to promote growth and entrepreneurship.

Republicans in Congress are currently aiming to pass the massive legislation and have it on Trump’s desk for signing by a self-imposed July 4 deadline.

Welcome to the award-winning Money Distilled newsletter. I’m John Stepek. Every week day I look at the biggest stories in markets and economics, and explain what it all means for your money.

Just a quick favour, if you’ve got time this lunchtime — it’s the last time I’ll ask, I promise — please help us out by filling in this questionnaire. Gloriously happy or deeply frustrated, we’d love to know how you feel your personal financial situation has changed in the last year.

Finished? OK, let’s turn to something that may well affect the personal financial situation of the UK dwellers among us.

A couple of days ago, I pointed out that the UK’s coalition government was heading for a split. When I used the term “coalition,” I was trying to convey the point — particularly for non-UK readers — that despite the Labour government’s landslide election victory last summer, it’s actually quite divided and that makes it harder to get certain things done.

It now seems that events have come to a head. Prime minister Keir Starmer has backed down on the disability benefit reforms that were meant to save the country £5 billion a year by 2030.

Instead, it seems that the new rules will only apply to new applicants. That raises questions and criticisms of its own (eg if the rules are unfair to existing claimants, in what way are they fair to new ones?) but so far reports suggest that it’ll win over enough rebels to help the government avoid a very damaging defeat Tuesday. (No guarantee though).

Now, there is a perfectly reasonable argument to be made that these reforms were poorly thought out. A more considered approach and a more detailed review of what’s going on might have revealed ways to save just as much money (or more) while avoiding cutting benefits from those who really do need them.

That appears to be a side-effect of the “more haste, less speed” approach to cuts that chancellor Rachel Reeves appears to have taken in her budget last year. So far that’s not worked out as she would have hoped. It’s resulted in not only this U-turn, but also a previous U-turn on winter fuel payments, and quite possibly a pending shift on non-dom taxation.

This presents the government with several problems. Firstly, the reason for taking these “tough” decisions was to stick to Reeves’s self-imposed fiscal rules. These actions were deemed necessary by the chancellor to avoid a repeat of the “Liz Truss” fiasco of October 2022.

The disability benefit reforms specifically were meant to save around £5 billion by 2030. Not a huge sum in the context of the government’s annual spending, but larger than the annual tax raised by stamp duty on shares, for example. And certainly significant in the context of a “£22 billion black hole”.

With the new changes, they won’t save as much. Ruth Curtice of the Resolution Foundation think tank reckons they’ll now save less than half of that.

That leads us to the second problem — the one of political authority. Basically, both Starmer and Reeves expended a great deal of political capital to push these changes past an uncomfortable back bench team. They’ve now been forced to change direction on both — winter fuel by the electorate, and disability payments by their own MPs.

In short, their “political trust” bank account is now overdrawn, which makes future “tough” decisions very difficult indeed. It also means that backbench wish list items — most notably the lifting of the two-child benefit cap — also become much harder to deny.

Which takes us to the third problem. If the fiscal rules need to be met (and that would probably be a U-turn too far, certainly if Reeves is to stay in post), then the government needs to find a way to plug the hole left by these and future demands.

As Paul Johnson, director at the Institute of Fiscal Studies, points out on X/Twitter, the big problem is that the U-turns and rebellions suggest that the the government simply can't make any cuts to spending. And in the absence of fiscal headroom, that “leaves taxes as only margin of adjustment.”

But that’s not easy either. In terms of the tax take as a percentage of GDP, the UK’s tax burden is already at a post-war high. So there is a question mark over how much higher it can realistically go, particularly if one wants to have a hope of carrying voters along.

(You can argue that it’s still relatively low compared to other nations, but this comparison is made somewhat trickier by differences in the way in which university education and also pensions are funded in other nations — this is something I hope to return to in a future letter — it’s an interesting subject).

The classic Jean-Baptiste Colbert line is that “the art of taxation consists in so plucking the goose as to obtain the largest possible amount of feathers with the least possible amount of hissing.” But we’re past that point. You’ve got a baldy, angry goose and whichever feather you pluck next, you have to expect to get your fingers pecked.

For example, if you really want to raise significant sums of money at this point — and if we’re now unable to cut Britain’s spending, then we’re going to need to — then you can’t just do it by soaking “the rich”. As my colleague Merryn points out, you need to broaden the tax base — perhaps by cutting the personal allowance, or raising the basic rate of income tax.

(This incidentally, is why populist party Reform UK’s promise to raise the personal allowance to £20,000 so that no one earning less than that pays tax, is so highly improbable).

Those really are tough choices. They won’t go down well on the doorstep. But the closer we get to autumn budget day, the more the state of the UK gilts market will loom large in the minds of investors.

It’s not that the “bond vigilantes” will suddenly materialise with baseball bats in hand, or anything so formal. But if Reeves can’t make her policies stick, and we return to the point where the UK is viewed as ungovernable, then the pressure will continue to build and the risk of a doom loop — and maybe another “Truss moment” — grows.

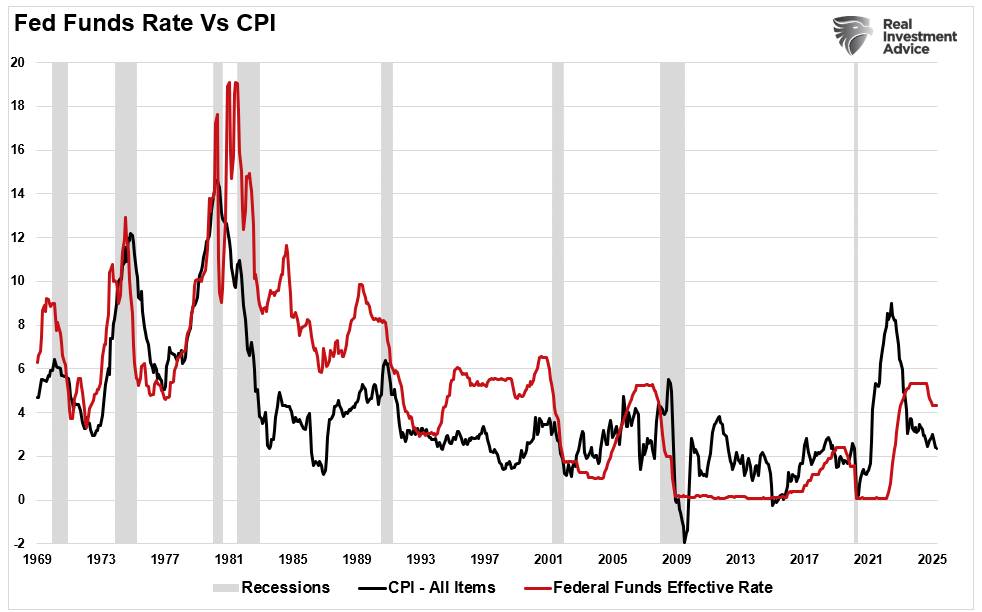

In 2023 and 2024, the Fed was under intense public and media scrutiny for calling the post-pandemic surge in inflation “transitory.” Critics argued that the Fed’s failure to anticipate the persistence and severity of rising prices undermined its credibility. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight and historical context, the Fed’s position wasn’t entirely misguided. Inflation proved temporary in a broader economic sense, and by 2025, the data confirmed a significant cooling of price pressures.

However, the Fed’s mistake wasn’t the “transitory” label—it was the Fed’s late response to raising interest rates and halting quantitative easing. As shown, the combined impact of the massive surge in the Government’s deficit spending (stimulus checks and infrastructure bills) and the Fed’s $120 billion monthly “quantitative easing” campaign caused a massive jump in economic growth and inflation.

However, instead of cutting back on stimulus when the economy rebounded, the Fed’s mistake was keeping its “foot on the gas” for too long. These delays allowed the inflationary fire to burn hotter and longer than necessary, exacerbated by an overlooked driver: excessive government spending.

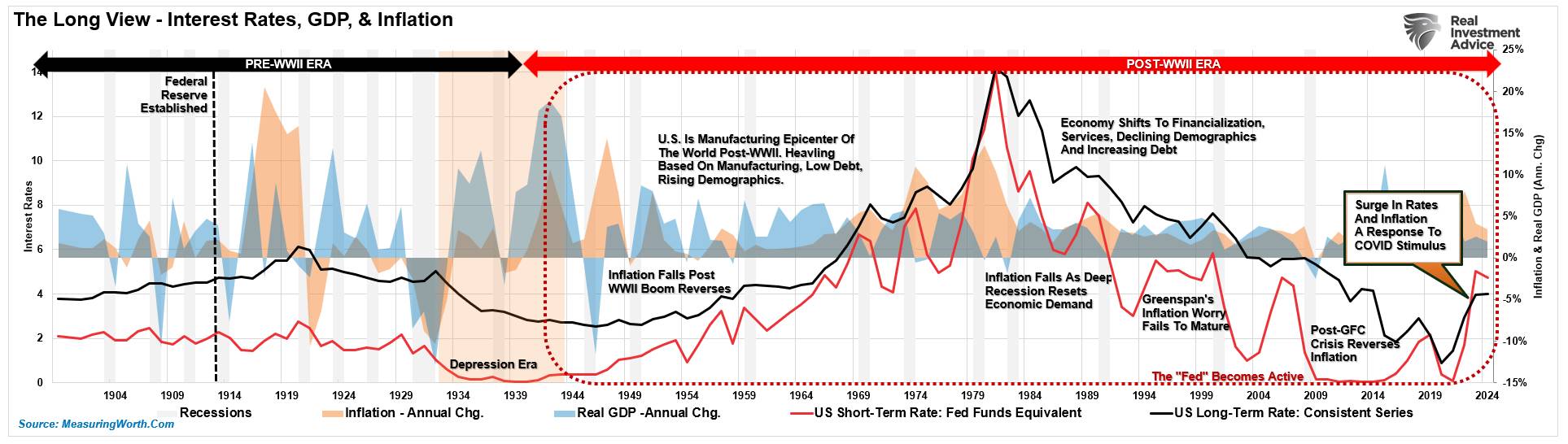

Despite the elevated levels of total economic stimulus, inflation and economic growth have subsided as the economy continues normalizing. However, to understand the Fed’s current policy risks, particularly in light of its recent warnings about tariffs, it’s essential to look back at past inflation spikes

U.S. economic history offers several instructive examples of inflationary episodes and how they eventually resolved.

Compared to these episodes, the COVID-driven inflation surge stands out for its rapid onset and similarly swift decline. Prices surged due to supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and historic stimulus. But by 2025, inflation is back to near-target levels. The duration of elevated inflation, from early 2021 through late 2023, was short by historical standards, and it faded as supply chains normalized and stimulus effects waned.

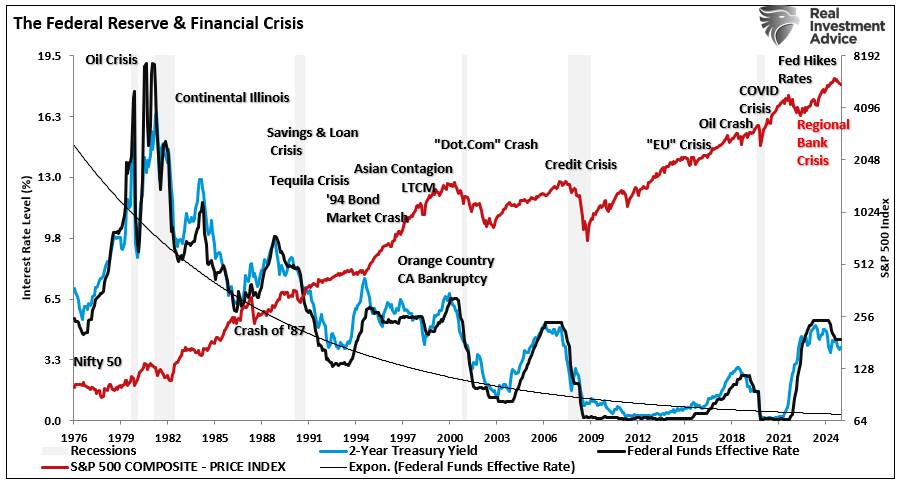

The historical shortcomings of the Fed’s actions, repeated policy mistakes, and flawed outlooks are clearly evident. The Fed hikes rates, creates an economic or credit-related event, and then cuts rates to fix it.

As such, investors should ask themselves why they are confident in the Fed’s current assessment of tariff-induced inflation risks.

The Fed’s Tariff Fears: Misreading the Present Through the Lens of the Past?

At the June 18, 2025, press conference, Fed Chair Jerome Powell expressed concern that rising tariffs could reignite inflation. With trade policy becoming increasingly protectionist, particularly toward China and Mexico, the Fed is wary that tariffs could push up import prices and thus overall inflation.

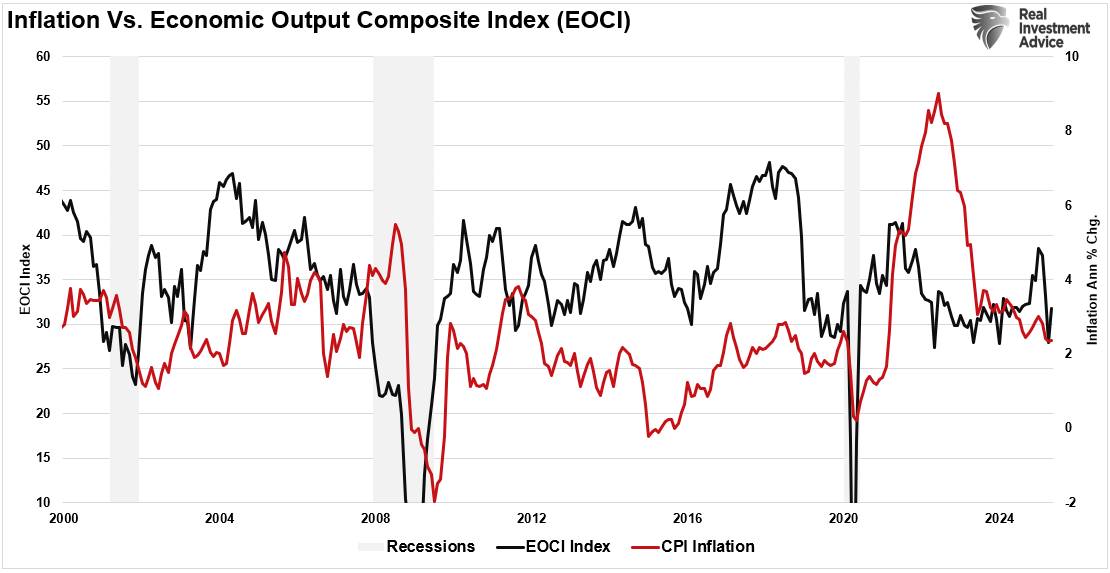

However, there’s an important distinction: inflation data from the last four months has shown no measurable impact from recent tariff actions. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) has remained stable or declined, while core inflation has softened. Meanwhile, job growth has slowed, and wage gains have moderated. All classic signs of a cooling economy.

This link between the economy and inflation is evident from the Economic Composite Index, which comprises nearly 100 hard and soft data points. Following the spike in economic activity post-pandemic, economic growth continues to decline. Given that inflation is solely a function of economic supply and demand, it is unsurprising that it continues to cool.

This raises a critical policy question: Is the Fed now over-compensating on the cautious side because of its past missteps with “transitory” inflation?

If so, the risk is that the Fed may once again make another policy mistake, as has repeatedly been the case in the past. After keeping rates too low for too long post-pandemic, policymakers might be too hesitant to cut rates, fearing another inflation flare-up that may never materialize. This fear-based approach risks undermining an already slowing economy.

Tariffs are designed to make foreign goods more expensive. However, supply chains and pricing are far more flexible in today’s globalized economy. If importers can shift production to tariff-free countries, renegotiate supplier contracts, or absorb costs to maintain market share, the inflationary effects of tariffs can be muted or even nonexistent. They are already doing this, as noted recently by CNN.

“The bonded warehouse route takes the opposite approach. Rather than mess with a good’s contents or move production elsewhere, businesses can import products from across the world without paying any tariffs when they enter the US — as long as they remain locked up in a special customs-regulated warehouse. Businesses can keep goods in these warehouses for up to five years without paying a tariff. They only pay the current tariff rate when they take goods out of storage. It’s a bet that tariff rates will go down in the short or medium term.”

Furthermore, companies are “reclassifying and redesigning” products to get lower tariff treatments.

“In other words, companies try to say their article or their good is something that gets low tariff treatment relative to what it might be, in essence. For example, Marvel successfully argued in court in 2003 that X-Men action figures are non-human toys (despite the premise of the franchise) rather than dolls, nearly halving their tax rate.” – NPR

Lastly, as discussed in “Tariff Risk Isn’t Inflation,” economists always forget the importance of consumer choice. The only payee of tariffs is the producers. Consumers can purchase less, delay, or exclude certain products from their consumption. To wit:

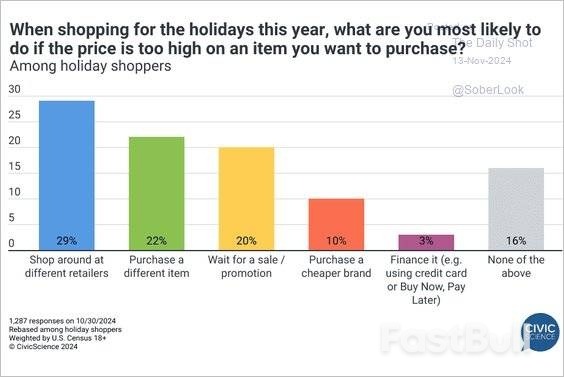

“Today, globalization and technology give consumers vast choices in the products they buy. While instituting a tariff on a set of products from China may indeed raise the prices of those specific products, consumers have easy choices for substitution. A recent survey by Civic Science showed an excellent example of why tariffs won’t increase prices (always a function of supply and demand).”

Of course, if demand drops for products with tariffs, prices will fall, reducing inflationary pressures.

Recent economic data suggests exactly that. Despite new levies on Chinese electric vehicles and Mexican steel, consumer durables and core goods prices have not moved materially higher. Businesses appear to be adapting quickly, with many shifting sourcing to Vietnam, India, or reshoring certain elements of production.

This raises the danger of a policy mismatch: If the Fed waits for inflation that doesn’t arrive, it may keep real interest rates excessively high for too long, just as it kept them too low following the pandemic. The consequences could be severe:

If the Fed is fighting a phantom threat, as Alan Greenspan did in the late 90s, and tariff-driven inflation never arrives, it could inadvertently engineer a downturn. And much like in 2021 and 2022, this would be a policy failure driven not by bad data, but by misjudging the economic environment.,

The Fed’s credibility rests not on never being wrong, but on being adaptive and forward-looking. Inflation has cooled, wage growth has moderated, and economic momentum is slowing. Now is the time for the Fed to focus not on headline fears, but on real-time data.

If tariffs have not yet translated into price increases, and employment indicators suggest slack is growing, the Fed should not delay necessary rate cuts to defend its credibility. Doing so risks repeating the mistake it made during the pandemic: ignoring the lagging effects of previous decisions.

Cutting rates too late would be just as damaging as hiking them too slowly.

The media mocked the Fed’s “transitory” narrative, but inflation was short-lived in the grand scheme. What mattered more was how long the Fed waited to act. With tariffs yet to trigger a real inflationary response and the economy showing signs of deceleration, the greater risk may be inaction, not inflation.

Investors should be alert to the Fed’s tendency to overcorrect past mistakes. Just as policy stayed too loose after COVID, it may now stay too tight for too long in 2025. Recognizing that monetary policy must adapt, not just react, will be key for policymakers and market participants navigating the road ahead.

India’s current account returned a better than expected surplus in the January-March quarter as trade deficit narrowed following the revision of gold import data.

The surplus in the broadest measure of trade in goods and services was $13.5 billion, or 1.3% of gross domestic product in the period, according to Reserve Bank of India data released Friday.

That compares with a median forecast of a $8.9 billion surplus by analysts in a Bloomberg survey, and a deficit of $11.3 billion in the October-December period.

The trade deficit for the quarter was at $59.5 billion, narrower than $79.3 billion in the October-December period. However, it was higher than the $52 billion in the year ago quarter.

The current account benefited from revisions in gold import data, but non-trade components, such as lower payments of investment income was a surprise, said Madhavi Arora, economist with Emkay Global Financial Services Ltd.

A current account surplus will ease pressure on the rupee that has been volatile in the past few weeks following rise in geopolitical conflicts.

Services exports increased year-on-year in major categories such as business services and computer services.

For the full fiscal year 2024-25, India’s current account deficit was $23.3 billion, or 0.6% of GDP, lower than $26 billion seen during fiscal 2023-24.

The head of Denmark's Arctic command said the prospect of a U.S. takeover of Greenland was not keeping him up at night after talks with a senior U.S. general last week but that more must be done to deter any Russian attack on the Arctic island.

U.S. President Donald Trump has repeatedly suggested the United States might acquire Greenland, a vast semi-autonomous Danish territory on the shortest route between North America and Europe vital for the U.S. ballistic missile warning system.

Trump has not ruled out taking the territory by force and, at a congressional hearing this month, Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth did not deny that such contingency plans exist.

Such a scenario "is absolutely not on my mind," Soren Andersen, head of Denmark's Joint Arctic Command, told Reuters in an interview, days after what he said was his first meeting with the general overseeing U.S. defence of the area.

"I sleep perfectly well at night," Anderson said. "Militarily, we work together, as we always have."

U.S. General Gregory Guillot visited the U.S. Pituffik Space Base in Greenland on June 19-20 for the first time since the U.S. moved Greenland oversight to the Northern command from its European command, the Northern Command said on Tuesday.

Andersen's interview with Reuters on Wednesday were his first detailed comments to media since his talks with Guillot, which coincided with Danish military exercises on Greenland involving one of its largest military presences since the Cold War.

Russian and Chinese state vessels have appeared unexpectedly around Greenland in the past and the Trump administration has accused Denmark of failing to keep it safe from potential incursions. Both countries have denied any such plans.

Andersen said the threat level to Greenland had not increased this year. "We don't see Russian or Chinese state ships up here," he said.

Denmark's permanent presence consists of four ageing inspection vessels, a small surveillance plane, and dog sled patrols tasked with monitoring an area four times the size of France.

Previously focused on demonstrating its presence and civilian tasks like search and rescue, and fishing inspection, the Joint Arctic Command is now shifting more towards territorial defence, Andersen said.

"In reality, Greenland is not that difficult to defend," he said. "Relatively few points need defending, and of course, we have a plan for that. NATO has a plan for that."

As part of the military exercises this month, Denmark has deployed a frigate, F-16s, special forces and extra troops, and increased surveillance around critical infrastructure. They would leave next week when the exercises end, Andersen said, adding that he would like to repeat them in the coming months.

"To keep this area conflict-free, we have to do more, we need to have a credible deterrent," he said. "If Russia starts to change its behaviour around Greenland, I have to be able to act on it."

In January, Denmark pledged over $2 billion to strengthen its Arctic defence, including new Arctic navy vessels, long-range drones, and satellite coverage. France offered to deploy troops to Greenland and EU's top military official said it made sense to station troops from EU countries there.

Around 20,000 people live in the capital Nuuk, with the rest of Greenland's 57,000 population spread across 71 towns, mostly on the west coast. The lack of infrastructure elsewhere is a deterrent in itself, Andersen said.

"If, for example, there were to be a Russian naval landing on the east coast, I think it wouldn't be long before such a military operation would turn into a rescue mission," he said.

White Label

Data API

Web Plug-ins

Poster Maker

Affiliate Program

The risk of loss in trading financial instruments such as stocks, FX, commodities, futures, bonds, ETFs and crypto can be substantial. You may sustain a total loss of the funds that you deposit with your broker. Therefore, you should carefully consider whether such trading is suitable for you in light of your circumstances and financial resources.

No decision to invest should be made without thoroughly conducting due diligence by yourself or consulting with your financial advisors. Our web content might not suit you since we don't know your financial conditions and investment needs. Our financial information might have latency or contain inaccuracy, so you should be fully responsible for any of your trading and investment decisions. The company will not be responsible for your capital loss.

Without getting permission from the website, you are not allowed to copy the website's graphics, texts, or trademarks. Intellectual property rights in the content or data incorporated into this website belong to its providers and exchange merchants.

Not Logged In

Log in to access more features

FastBull Membership

Not yet

Purchase

Log In

Sign Up