Markets

News

Analysis

User

24/7

Economic Calendar

Education

Data

- Names

- Latest

- Prev

Signal Accounts for Members

All Signal Accounts

All Contests

U.K. Trade Balance Non-EU (SA) (Oct)

U.K. Trade Balance Non-EU (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Trade Balance (Oct)

U.K. Trade Balance (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Services Index MoM

U.K. Services Index MoMA:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Construction Output MoM (SA) (Oct)

U.K. Construction Output MoM (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Industrial Output YoY (Oct)

U.K. Industrial Output YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Trade Balance (SA) (Oct)

U.K. Trade Balance (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Trade Balance EU (SA) (Oct)

U.K. Trade Balance EU (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Manufacturing Output YoY (Oct)

U.K. Manufacturing Output YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. GDP MoM (Oct)

U.K. GDP MoM (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. GDP YoY (SA) (Oct)

U.K. GDP YoY (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Industrial Output MoM (Oct)

U.K. Industrial Output MoM (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Construction Output YoY (Oct)

U.K. Construction Output YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

France HICP Final MoM (Nov)

France HICP Final MoM (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Outstanding Loans Growth YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland Outstanding Loans Growth YoY (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M2 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M2 Money Supply YoY (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M0 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M0 Money Supply YoY (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland M1 Money Supply YoY (Nov)

China, Mainland M1 Money Supply YoY (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

India CPI YoY (Nov)

India CPI YoY (Nov)A:--

F: --

P: --

India Deposit Gowth YoY

India Deposit Gowth YoYA:--

F: --

P: --

Brazil Services Growth YoY (Oct)

Brazil Services Growth YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Mexico Industrial Output YoY (Oct)

Mexico Industrial Output YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Russia Trade Balance (Oct)

Russia Trade Balance (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Philadelphia Fed President Henry Paulson delivers a speech

Philadelphia Fed President Henry Paulson delivers a speech Canada Building Permits MoM (SA) (Oct)

Canada Building Permits MoM (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Wholesale Sales YoY (Oct)

Canada Wholesale Sales YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Wholesale Inventory MoM (Oct)

Canada Wholesale Inventory MoM (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Wholesale Inventory YoY (Oct)

Canada Wholesale Inventory YoY (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Canada Wholesale Sales MoM (SA) (Oct)

Canada Wholesale Sales MoM (SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

Germany Current Account (Not SA) (Oct)

Germany Current Account (Not SA) (Oct)A:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Weekly Total Rig Count

U.S. Weekly Total Rig CountA:--

F: --

P: --

U.S. Weekly Total Oil Rig Count

U.S. Weekly Total Oil Rig CountA:--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Large Non-Manufacturing Diffusion Index (Q4)

Japan Tankan Large Non-Manufacturing Diffusion Index (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Small Manufacturing Outlook Index (Q4)

Japan Tankan Small Manufacturing Outlook Index (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Large Non-Manufacturing Outlook Index (Q4)

Japan Tankan Large Non-Manufacturing Outlook Index (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Large Manufacturing Outlook Index (Q4)

Japan Tankan Large Manufacturing Outlook Index (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Small Manufacturing Diffusion Index (Q4)

Japan Tankan Small Manufacturing Diffusion Index (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Large Manufacturing Diffusion Index (Q4)

Japan Tankan Large Manufacturing Diffusion Index (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

Japan Tankan Large-Enterprise Capital Expenditure YoY (Q4)

Japan Tankan Large-Enterprise Capital Expenditure YoY (Q4)--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Rightmove House Price Index YoY (Dec)

U.K. Rightmove House Price Index YoY (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Industrial Output YoY (YTD) (Nov)

China, Mainland Industrial Output YoY (YTD) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

China, Mainland Urban Area Unemployment Rate (Nov)

China, Mainland Urban Area Unemployment Rate (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Saudi Arabia CPI YoY (Nov)

Saudi Arabia CPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Euro Zone Industrial Output YoY (Oct)

Euro Zone Industrial Output YoY (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

Euro Zone Industrial Output MoM (Oct)

Euro Zone Industrial Output MoM (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Existing Home Sales MoM (Nov)

Canada Existing Home Sales MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Euro Zone Total Reserve Assets (Nov)

Euro Zone Total Reserve Assets (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.K. Inflation Rate Expectations

U.K. Inflation Rate Expectations--

F: --

P: --

Canada National Economic Confidence Index

Canada National Economic Confidence Index--

F: --

P: --

Canada New Housing Starts (Nov)

Canada New Housing Starts (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. NY Fed Manufacturing Employment Index (Dec)

U.S. NY Fed Manufacturing Employment Index (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

U.S. NY Fed Manufacturing Index (Dec)

U.S. NY Fed Manufacturing Index (Dec)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Core CPI YoY (Nov)

Canada Core CPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Manufacturing Unfilled Orders MoM (Oct)

Canada Manufacturing Unfilled Orders MoM (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Manufacturing New Orders MoM (Oct)

Canada Manufacturing New Orders MoM (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Core CPI MoM (Nov)

Canada Core CPI MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Manufacturing Inventory MoM (Oct)

Canada Manufacturing Inventory MoM (Oct)--

F: --

P: --

Canada CPI YoY (Nov)

Canada CPI YoY (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Canada CPI MoM (Nov)

Canada CPI MoM (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Canada CPI YoY (SA) (Nov)

Canada CPI YoY (SA) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

Canada Core CPI MoM (SA) (Nov)

Canada Core CPI MoM (SA) (Nov)--

F: --

P: --

No matching data

Latest Views

Latest Views

Trending Topics

Top Columnists

Latest Update

White Label

Data API

Web Plug-ins

Affiliate Program

View All

No data

U.S. tariffs on imported gold bars shocked global markets, spiking New York futures and disrupting trade flows. The move impacts Swiss exports and may face legal challenges amid growing uncertainty.

The price of gold futures have soared to a record high after it was reported that the US would put tariffs on imports of 1kg bars in a further trade blow to Switzerland, which dominates the world’s refining industry.

Swiss exports to the US were hit by a crippling 39% tariff on Thursday after the country’s president returned empty-handed from a last-minute dash to Washington in an attempt to get the rate, among the highest imposed by Donald Trump, lowered.

It has subsequently emerged that US customs recommended that certain imports of gold bars that had been in a tariff exemption category should also be covered by the 39% rate.

The detail in a ruling letter – used by the US to clarify its trade policy – was signed on 31 July and seen by the Financial Times.

The price of gold futures for delivery in December hit an all-time intraday high of $3,534 (£2,630) after the news emerged.

Christoph Wild, the president of the Swiss Association of Manufacturers and Traders of Precious Metals, told the Financial Times that the ruling dealt “another blow” to the Swiss gold trade with the US and went against the prevailing view that gold would be exempt.

With about 70% of the world market, Switzerland dominates the trade of turning gold from mines and other sources into gold bars. The precious metal is also one of its biggest exports to the US along with pharmaceuticals.

The gold trade is usually circular between London, New York and Switzerland, with bars cast and recast in different sizes according to orders.

Switzerland imports about 2,000 tonnes of gold annually, much of it from intermediary banks in London, New York and elsewhere, which are later exported as gold is seen as a safe haven investment at a time of financial uncertainty.

In the 12 months to June, Swiss exports of gold to the US were worth about $61.5bn and this now faces an extra levy of 39%. Switzerland’s rate is among the highest in the world, after Brazil, Syria, Laos and Myanmar.

Gold prices had already jumped about 25% this year as investors sought a safe haven from the turmoil caused in the markets by Trump’s tariffs.

High net worth Americans are among those turning to physical gold, which can be held in vaults in the Swiss Alps for an extra cost.

According to reports, gold bars were in such demand in the US in May after Trump’s announcement of sweeping “reciprocal” tariffs the previous month that Costco capped how many gold bars could be bought in a day.

Switzerland has been blindsided by Trump’s decision to single them out for punitive tariffs and industry leaders are already talking about the possibility of imposing short working weeks on workers in export businesses.

The minutia of tariff changes, bond-market volatility or reallocation of supply chains creates a smoke screen for businesspeople who depend on stability and predictability to make decisions and deals on a daily basis. Sudden changes can swiftly undo progress.In geopolitics, wars and clashes also seem to quickly flare up and finish just as suddenly, as evidenced by the United States’ intervention in the Israel-Iran rocket strikes in June. The frequent doses of upheaval in recent months are described by many as “uncertainty.”Geopolitical observers, however, are aware of a continually changing landscape, characterized by four features.

First, the current state of the world resembles a pre-World War II or even a pre-World War I context, rather than the Cold War and its “strategic stability,” namely the struggle for ideological supremacy tempered by the threat of mutually assured nuclear destruction. Today, China and Russia seek to counterbalance the U.S., which itself is striving to reassert its dominance. Meanwhile, the rest of the world is striking out on its own. This makes the situation more volatile and dangerous than during the Cold War. Heightened insecurity then feeds into muscular militarization and an armament race.As the U.S. and China − the leading actors in globalization and each increasing its share of mutual prosperity − began to find themselves as rivals and adversaries countering each other’s power and influence, de-risking and de-coupling became the norm. Strategic enemies can hardly be dependent on each other’s supply chains.

Former U.S. President Barack Obama’s Asia-Pacific pivot, President Donald Trump’s first administration’s focus on Indo-Pacific alliances and the Biden administration’s maintenance of Mr. Trump’s hardening tariff policy on China were key signs of this strategic shift.The Trump administration’s tariffs on China are more a reflection of a geopolitical standoff rather than just mercantilist economic policies aimed at encouraging domestic production.

Regardless of the negotiated outcome of the current spate of tariff brinksmanship, the trend of de-risking supply chains to ensure that products critical for society (not necessarily even military in nature) cannot be held hostage will continue. In the same manner, technology exchanges that could advance the adversary’s potential will be under increased export controls.Hence, the second Trump administration’s tariffs on China are more a reflection and tool of a geopolitical standoff rather than just mercantilist economic policies aimed at encouraging domestic production, as they are very often portrayed and understood.

This is the essence of the misperception among many economic analysts when discussing the events of recent months. They tend to assess the economic rationale and impact, discounting the driving force of recent events: geopolitics and domestic politics.

Second, current events seem to mirror the era of Japan’s rise to become the largest exporter to the U.S. in the 1960-1980s, and its “lost decade” of economic stagnation that struck in the early 1990s. American policies were created to counter the “unfair” devaluation of the Japanese yen, which supported cheaper Japanese exports. Voluntary export restrictions were initially agreed upon by Japan and the U.S. to provide the American auto industry time to restructure and increase competitiveness. At the same time, Japanese automakers began to invest in U.S. production, and Japan itself decreased non-tariff trade barriers to ease the access of U.S. imports. All of these elements echo the current rhetoric in Washington on U.S. trade relations with China, the European Union, Japan and others.

It is no coincidence that President Trump and his officials highlight car and steel imports and their impact on local production and employment. Whether it is economically justifiable or not, the logic remains the same as four decades ago: Workers in these industries are impacted by cheaper imports, which translates into political pressure in such electorally consequential U.S. states as Michigan, Pennsylvania or North Carolina. This also explains why American political opposition to and criticism of tariff hikes is rather meek and primarily focuses on the increase in domestic prices, rather than blaming the overall strategy, or lack thereof, for these actions.

As the origin of Mr. Trump’s tariff policy is political rather than economic, any discourse on the welfare effects of these actions is likely to have little impact on the calculations of those devising them. Shrimp will not be less expensive in the Southern Atlantic coastline of the U.S. as a result of any trade deal with Vietnam, cars from Detroit which sell well in Texas will not sell better in Japan or Germany. Instead, the policies fulfill a political objective targeting those specific constituents who demanded such actions to protect their local markets.

Looking back at the 1980s, voluntary export restrictions on Japanese cars were intended for three years, but lasted 13 and ended only with the conclusion of Uruguay Round negotiations on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in 1994. The negotiations themselves lasted for eight years, despite being undertaken among allies such as the U.S., Japan and the EU, with minor interjections from developing countries.

The end of the voluntary restrictions came right around the time when Japanese car producers finished setting up their production in the U.S. In the meantime, the North American Free Trade Agreement was signed in 1992 and came into effect in 1994. Also, the European single market that was initially created in 1986 became the European Union in 1993. These parallel developments give a taste of coalescing globalizing forces that finally brought about the demise of protectionism. They also give clues as to how long the current trend of erecting trade barriers could last.

The outcome of trade negotiations in the Trump era is likely to be defined by geopolitical rivalry. As mentioned above, the largest trade deal in history thus far, the Uruguay Round of GATT, was concluded among like-minded allies mostly during the U.S.-dominated unipolar moment. In contrast, the driver of today’s economic policies is geopolitical rivalry aided by domestic expediency, and this, rather than the pursuit of efficiency and profit, will dictate the direction of policy in the foreseeable future.

Third, China is already feeling the downward spiral of property prices and bond yields. Any sign of attempting to force certain restrictions upon Beijing could be interpreted by Chinese leaders as an effort to stall the country’s growth and push it down the path of a deflationary spiral, resembling the “lost decade” in Japan. Negotiations with the U.S. and its allies will be complicated by this geopolitical undercurrent.A lot depends on the EU’s reaction to American tariffs, since Brussels can be an initiator and a medium for multilateral negotiations. The very origin of the EU was to promote peace through greater trade, so the organization might be suited both in terms of capacity and ideology to undertake such a task, especially reforming the World Trade Organization.

Fourth, it is interesting how traditional analysis of the current trade and geopolitical environment tends to overestimate the impact of existing institutions while overlooking the impact of the personality of the leaders themselves.This shift from party- and institution- to person-centered leadership is usually is discussed in reference to President Trump. However, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Chinese President Xi Jinping were initially perceived as business-as-usual leaders, even “liberal reformers” of sorts, but were later seen as dramatic departures from the past. In this current state of affairs, close attention should be paid to the leaders, not only institutions.

As evidenced recently, such leaders, even in the most stable institutional settings, can bring radical change to alliances and fundamentally alter the direction of economic policies. Their rhetoric, past experiences and changing world views are of oversized impact in this world of shifting geopolitical alliances. The analysis of the personalized, historical and cultural contexts of the decision-making of great powers − usually the purview of international relations and country-specific researchers, and considered “unscientific” by economic analysis − escapes analytics based on institutional tools. In contemporary political debate and in business, much more emphasis should be placed on this “unscientific” reality.

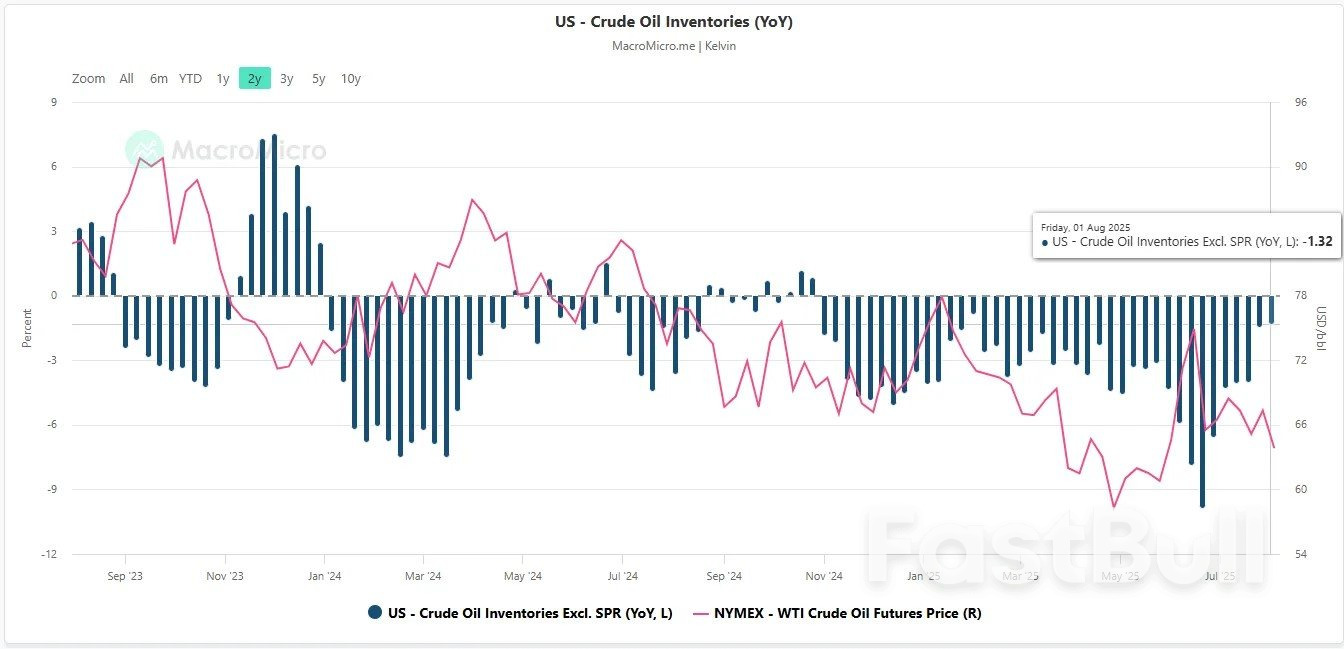

Fig. 1: EIA US crude oil inventories excluding SPR (y/y change) with WTI crude oil futures as of 1 Aug 2025

Fig. 1: EIA US crude oil inventories excluding SPR (y/y change) with WTI crude oil futures as of 1 Aug 2025 Fig. 2: West Texas Oil CFD medium-term trend as of 8 Aug 2025

Fig. 2: West Texas Oil CFD medium-term trend as of 8 Aug 2025The Canadian economy lost the most jobs since January 2022, and excluding the pandemic, it's the largest drop in seven years.

Employment fell by 40,800 positions in July, driven by decreases in full-time work, while the jobless rate held firm at 6.9%, Statistics Canada data showed Friday. The number of job losses surpassed even the most pessimistic projection in a Bloomberg survey of economists.

The monthly decline was concentrated among youth ages 15 to 24, who are usually among the first to experience a labor-market downturn. Their unemployment rate reached 14.6%, the highest since September 2010 outside of the pandemic. The employment rate for youth fell to the lowest since November 1998, excluding the years impacted by Covid-19.

The Canadian labor market failed to sustain its strong momentum from June, when it surprisingly added the most jobs in six months. The Bank of Canada held its policy interest rate at 2.75% for a third straight meeting last week, but said the labor market remains soft, with the unemployment rate rising from 6.6% at the beginning of the year.

Of the 1.6 million people who were unemployed in July, 23.8% had been continuously searching for work for 27 weeks or more. This was the highest share of long-term employment since February 1998, not including the pandemic.

Compared with a year earlier, unemployed job searchers were more likely to remain jobless from one month to the next. Nearly 65% of those who were unemployed in June remained so in July, versus 56.8% from a year ago. The layoff rate, however, was virtually unchanged.

The employment rate -- the proportion of the working-age population that’s employed -- fell 0.2 percentage points to 60.7% in July. It was down 0.4 percentage points from the start of this year.

The private sector lost 39,000 jobs last month, and public-sector employment was little changed. Job losses were driven by information, culture and recreation, as well as construction and business, building and other support services. Transportation and warehousing added jobs for the first time since January.

Employment fell in Alberta and British Columbia, while it was virtually unchanged in Ontario and held steady in Quebec. Saskatchewan was the only province to record job increases in July.

Total hours worked fell 0.2% in July, and were up 0.3% from a year earlier.

Yearly wage growth for permanent employees accelerated to 3.5%, from 3.2%, versus economist expectations for compensation gains to slow to 3.1%.

White Label

Data API

Web Plug-ins

Poster Maker

Affiliate Program

The risk of loss in trading financial instruments such as stocks, FX, commodities, futures, bonds, ETFs and crypto can be substantial. You may sustain a total loss of the funds that you deposit with your broker. Therefore, you should carefully consider whether such trading is suitable for you in light of your circumstances and financial resources.

No decision to invest should be made without thoroughly conducting due diligence by yourself or consulting with your financial advisors. Our web content might not suit you since we don't know your financial conditions and investment needs. Our financial information might have latency or contain inaccuracy, so you should be fully responsible for any of your trading and investment decisions. The company will not be responsible for your capital loss.

Without getting permission from the website, you are not allowed to copy the website's graphics, texts, or trademarks. Intellectual property rights in the content or data incorporated into this website belong to its providers and exchange merchants.

Not Logged In

Log in to access more features

FastBull Membership

Not yet

Purchase

Log In

Sign Up